Goodbye Pi-hole. Hello CoreDNS.

12 Jun 2022 ad-blocking · dns · internetI understand the economics behind advertising. Advertising can be used to subsidize content. However, I refuse to accept that Bloomberg.com needs to show advertisements to a paying subscriber.1 This comes down to personal preference: If you believe that advertisements are a net good and support the work that you are viewing “for free”, so be it. I do not believe that. If I must pay for content that is ostensibly “free” by having my attention distracted by an advertisement which I did not ask for and am not interested in, then I reserve the right to use every tool in my arsenal to avoid seeing the advertisement. All of this is just a preamble to a recent change I made in one of the central components that I use to browse the Internet: my DNS server. I switched from Pi-hole, a popular adblocking DNS server, to CoreDNS and a plugin for ad blocking which I wrote. This is a post about why I decided to reinvent the wheel.

Why Should You Run Your Own DNS Server?

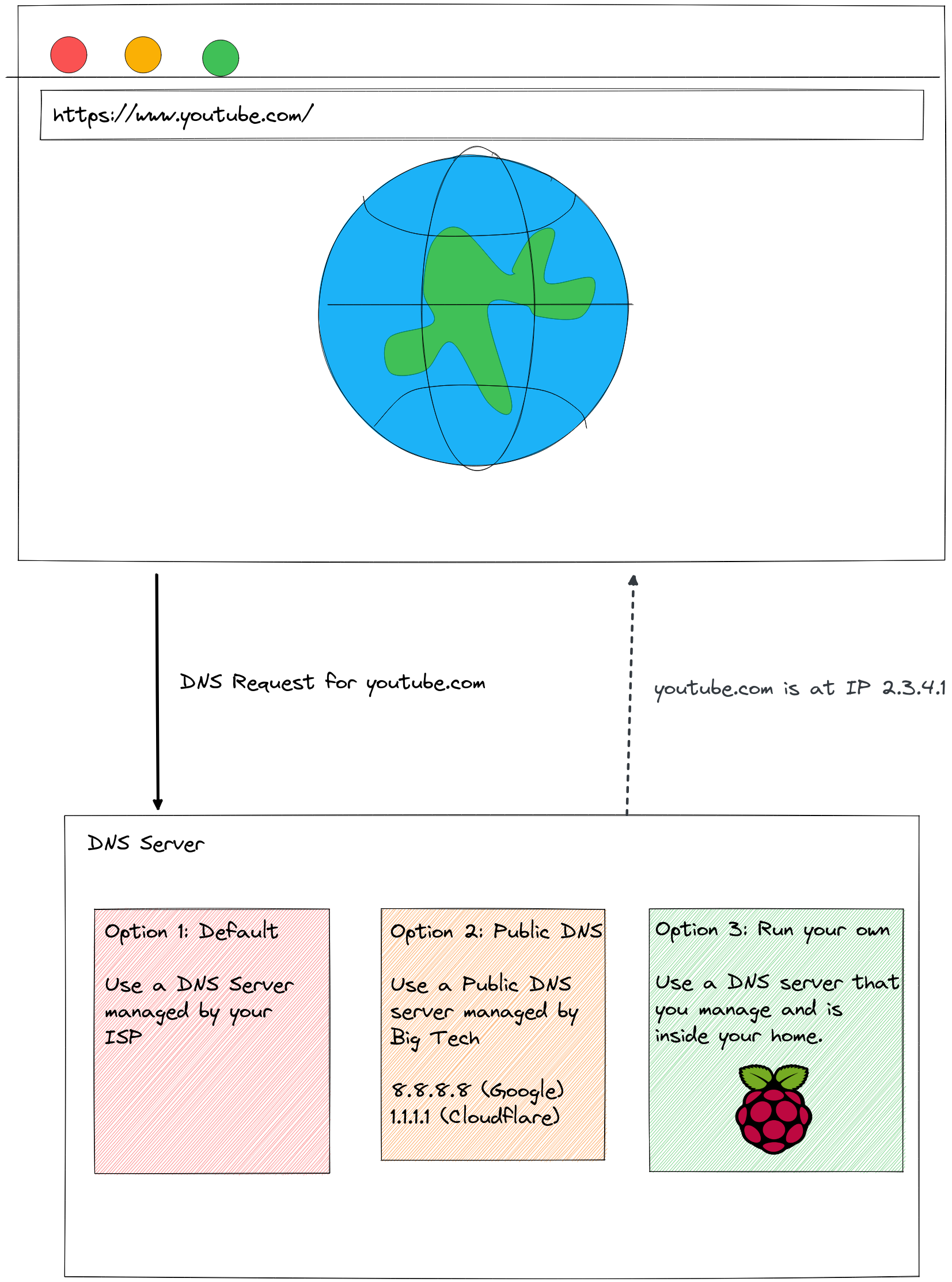

DNS (Domain Name System) is a key part of the infrastructure that makes up the backbone of the

Internet. It is also the most decentralized part of it. Most people use a DNS server which is a few

kilometers away from them. Internet Service Providers (ISP) will generally send default

configuration to their clients which will point them to DNS servers run by the ISP. This allows the

ISP to make a list of websites that their users are using and possibly use it as leverage when

negotiating with service providers about preferential treatment. However, the clients that users use

to browse the Internet (their web browser or their computer’s operating system) have the ability to

override this setting and specify their own DNS server. Public DNS servers have been on the rise:

Google’s 8.8.8.8 and Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 are popular alternatives. These DNS servers have a

significant improvement: They are far more reliable compared to your local ISP’s DNS

server. However, data about your Internet traffic continues to be sent to someone. To make the

situation worse, DNS traffic is mostly served over UDP. UDP is an insecure protocol which does not

protect information in transit. (Not “HTTPS,” if you will.) So, your ISP still has access to the

list of websites you are visiting. The solution to all of these problems is hosting your own DNS

server on a Raspberry Pi computer inside your home. (A recent improvement over the old design of

UDP-based DNS is DNS-over-HTTPS. This ensures that DNS traffic can not be snooped upon, in transit.)

So, there’s one advantage: Your DNS request, which contains the name of the website that you are visiting, does not leave your home. Your ISP has no clue where your traffic is going. (They can figure it out using the IP address that your packet is headed for, but this is harder and ISPs have a tendency to aim for the low-hanging fruit and not spend too much time trying to track their users, if the information is not handed to them on a platter.)

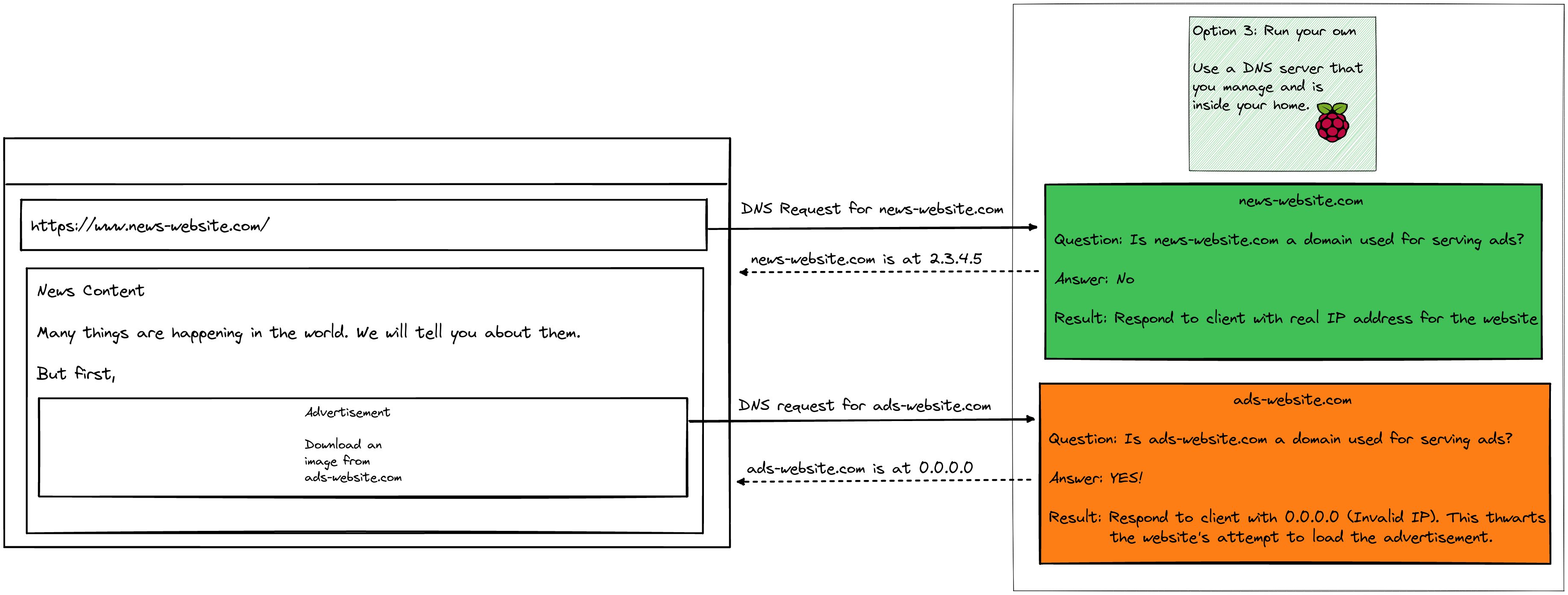

There is another advantage: If you don’t like the domain inside the DNS request, then you can stop the request in its tracks and prevent the client from fetching what it wants to fetch. Your browser loads a page (for example, a news website). The news website has a script which will call an advertising server and request the ad which will be placed in the box in between paragraphs. If you could identify just these requests to the advertising server and block them somehow, then the website will not be able to show you ads!

One idea is to create a list of the IP addresses that are used by advertising servers around the world and block any request which is bound to these servers. This is hard and not reliable enough because IP addresses change a lot and the process for changing them can be easily automated.

Another idea is to list the domains which these servers are on and block any DNS request for these domains! This approach is convenient and reliable: Changing domains is hard and even if domains are changed, if you don’t want anything on the domain, then you can simply add the new domain to your blocklist. (Changing domains is hard primarily because each new domain has to be registered with a domain registrar and this requires a small fee. The fee must be paid and payment to vendors on demand is hard to automate. Also, so few users are using ad-blocking DNS servers that the return-on-investment for an automated domain changing system is limited.)

So, we have a good approach. But we are missing one key component: The list of domains which we want to block. There are many excellent lists out there and I recommend this one. It lists about 1 million domains and it is updated frequently. It is an aggregation of other lists and works well. (I have used it along with another list for the past several months, and I have not had any domain which I wanted to send traffic to blocked due to a domain being mistakenly added to the list.2)

Now, we have a list of domains that we want to block and the approach that we are going to use to block the domains (a DNS server which can look at this list and block requests which match a domain in the blocklist.) Now, we need to search for the software which will implement our solution.

Why CoreDNS?

There are many options. The most popular one is Pi-hole, I used it for a few months and realized that I could not continue using it because I disagreed with its GUI-centric design philosophy and the effect that this philosophy had on its purpose: being a good DNS server. CoreDNS is a DNS server which puts plugins front-and-center and encourages its users to write their own plugins. It is written in a programming language that I like and am familiar with, and I don’t mind maintaining a plugin in the long term.

Pi-hole

Pi-hole is written in the programming language C. I chose it, as I believed that it was built for running on a Raspberry Pi. (I did not research how it was built or why it would run well on a Raspberry Pi.) It was fairly easy to set up on a Raspberry Pi. There were some manual steps during the setup process and it could not be fully automated. However, this was not a big problem for me because I did not believe that I would need to repeat this setup process.

I started noticing problems with Pi-hole almost immediately after setting it up. The main problem seemed to be with its statistics reporting module. The sane way to report statistics is to provide an API endpoint which can be scraped periodically. This API endpoint should either take the starting time for statistics or have a configurable time period, which can be passed as a parameter to the request. Pi-hole had a strange 24 hour pre-configured time window. I was not sure why it was 24 hours or why it is pre-configured.

I was convinced that this was going to be a deal-breaker for me. The only thing I wanted my DNS server to report was the number of requests that it blocked and the number of requests that it forwarded to the upstream DNS server. This value could be wrangled out of Pi-hole and I figured out how to do it. I had to dive deep into Pi-hole’s C code. There isn’t that much of it and I was able to read it all over a few hours. I had to make 2 pull requests to use the existing configuration variables. These configuration variables were not respected by the application code; a bad sign for a well-maintained codebase.

With these patches, I had managed to get the statistics that I wanted. Perhaps, I should have stopped here.

However, the more I thought about what Pi-hole was really doing, I realized that its only reason for existence was statistics collection. Indeed, the whole repository was a large wrapper around Unbound, a full-featured DNS resolver. All Pi-hole did was maintain a few counters which it incremented based on the requests that it received/blocked. The statistics that it collected were supposed to be displayed on a GUI dashboard. This dashboard is the reason for the mysterious “24 hour” value above. The code for these counters was not stellar either: There were many global variables and there seemed to be very little of the neat dependency injection that I am used to.

I did not like this design. A blocklist-enabled DNS server should do one thing and one thing well3: Serve DNS requests and block the ones that the user does not want to serve. To plaster a GUI onto this server and change the code inside to fit it to the needs of the GUI is a bad idea, in my opinion. If users want a GUI, then they should use the statistics that are reported by the DNS server and make their own GUI. At the very least, the GUI should be an optional part of the DNS server and no code or decisions made inside the DNS server should be to please the GUI user.

Pi-hole did not follow any of these principles. Most of the code inside the repository was primarily to make the GUI better looking. One of the patches I made ended up creating a bug for most users of the Pi-hole GUI because it changed the way that time slots were stored. Instead of storing statistics for the “24 hours until now” when the server starts, I proposed storing the “24 hours from the start of the server.” My approach would make sense if the server had to store the statistics only to report it to the user as a number. If the statistics are part of a GUI, then when the server starts, the user will see a jarring empty graph with the current time on the left side of the horizontal axis, with the future 24 hours with no data.

This bug which my innocent PR to improve statistics reporting had caused put me over the top. I decided to change my DNS software because I could not live with this C code which was not designed in a way that I approved of and had a lot of code to satisfy GUI users, when I knew for a fact that I was never going to use the GUI bundled with a DNS server.

CoreDNS

CoreDNS is a DNS server written in Golang. It is not a recursive DNS resolver. Indeed, it does not do anything related to the recursive process required to resole DNS queries. However, it does everything that is essential before and after this core part of the DNS resolution process. Most importantly, CoreDNS is built with plugins in mind; it provides first-class support for preexisting plugins as well as plugins written by the user.

Another advantage to keep in mind is that CoreDNS has excellent built-in support for metrics collection. It is designed to be run inside environments like Kubernetes, where metrics collection is not an afterthought. Specifically, CoreDNS integrates with the popular monitoring server Prometheus. More on this later.

The plugin API is intuitive. Every DNS request passes through a series of plugins. By controlling the order in which these plugins operate, it is possible to change the input or the output of these DNS requests. And any plugin can return a response to the user. All the heavy-lifting required to keep track of plugins, integrate with each plugin and call them at the appropriate time, identify whether the plugin is going to respond or simply fall through to the next plugin is done by CoreDNS. Plugin writers have to care about a single function: This function receives a DNS request as input, and the plugin writer’s responsibility is to either set a response to this request or to return an error code indicating that the request should not be passed to the next plugin in the plugin chain.

Another (incidental) advantage is that I have been using Golang at work for the past 4 years. My familiarity with the programming language is quite high and I was happy to write and maintain a CoreDNS plugin. I hoped to learn more about the nitty-grity of DNS implementations, and common pitfalls that one might fall into along the way.

So, over 2 days, I wrote a CoreDNS plugin to block domains based on a file and Ansible configuration to deploy this plugin alongwith the main CoreDNS application to my Raspberry Pi. The process of writing the plugin was good. I started with the coredns/example plugin provided by CoreDNS’ authors. This plugin shows other plugin writers what to think about and how to architect their plugin. After a few hours of understanding how plugins really worked, I was able to get a working prototype with a hardcoded list of domains. Switching out the hardcoded source of domains with a file on the local file store was easy. The most confusing part of the process was understanding where the order of plugin execution was defined. I understood this process after reading the excellent blog post from CoreDNS’ authors: How Queries are Processed in CoreDNS.

Other Options

AdGuardDNS is the closest alternative to what I built. The DNS server is a fork of CoreDNS and it uses a bunch of plugins built and maintained by AdGuard. I don’t have a good reason for not using this. One of my friends uses this on their Raspberry Pi and they recommended it to me. I looked into it and decided not to use it mostly on a whim: AdGuard is a business that sells an AdBlocker and VPN software.4 The DNS server is a part of their offerings. While the DNS server is open source right now, there is some discussion about how future features might not be added to their open source offering, prioritizing the paid alternative instead.

We use AdGuard DNS functionality as a part of other AdGuard software, most of which are distributed on a pay-to-use basis. We might also develop a paid version of AdGuard DNS based on the current one, more advanced and with more features. – AdguardTeam/AdguardDNS’ README. Section: “Why is AdGuard DNS free? What’s the catch?”

My coworker @execjosh’s mydns is another blocklist-enabled DNS server. It has a lot of logic which was not a part of my CoreDNS plugin because all the request handling was outsourced to DNS. I used mydns as a reference for implementing the tricky parts of DNS: Setting the reply and understanding more about DNS question types/classes.

Improved Metrics Collection

So, did my monitoring problem get solved? Yes. Bonus: I did not have to write any code to solve it.

CoreDNS comes with a metrics plugin. This plugin reports metrics in the Prometheus format. Having worked with Prometheus servers inside Kubernetes for the past few years, I am familiar with this format and I marvel at its simplicity.

Getting the number of blocked and forwarded requests from a Prometheus-compliant metrics endpoint is very very simple.

pi@dns-1:~ $ curl localhost:9153/metrics -s | grep dns_responses_total

# HELP coredns_dns_responses_total Counter of response status codes.

# TYPE coredns_dns_responses_total counter

coredns_dns_responses_total{plugin="",rcode="SERVFAIL",server="dns://:53",zone="."} 458

coredns_dns_responses_total{plugin="blocker",rcode="NOERROR",server="dns://:53",zone="."} 5191

coredns_dns_responses_total{plugin="forward",rcode="NOERROR",server="dns://:53",zone="."} 218955

coredns_dns_responses_total{plugin="forward",rcode="NXDOMAIN",server="dns://:53",zone="."} 2073

coredns_dns_responses_total{plugin="forward",rcode="REFUSED",server="dns://:53",zone="."} 2232

coredns_dns_responses_total{plugin="forward",rcode="SERVFAIL",server="dns://:53",zone="."} 426

Using the plugin= part of this output, I can see that 5191 DNS requests were blocked by the

server. 218,955 DNS requests were forwarded to the upstream DNS server (an Unbound instance running

on the same Raspberry Pi.) Forwarded requests faced some errors like “Non-Existent Domain”

(NXDOMAIN) or “Server Failure” (SERVFAIL).

If I were to run Prometheus on the Raspberry Pi, I would be able to collect these metrics easily and use Grafana to visualize them. However, I don’t think that I will be doing that. The Raspberry Pi uses flash memory and is severely limited in terms of disk read/write throughput. The DNS server itself will rarely read from disk; it needs to read the blocklist file from disk periodically. I am interested in only one metric from the CoreDNS server, so I believe that I will continue to use an external monitoring tool such as Mackerel or a local Round Robin Database, which is more typical for networking infrastructure.

-

Bloomberg subscriptions cost $35 per month. ↩

-

The only domain that came close was related to Bloomberg and its emails. This domain was included in the lists as a domain that serves ads, but it was a domain which is used for links inside newsletters sent by Bloomberg via email, and is a tracking domain indeed. It redirects to the main Bloomberg.com website. ↩

-

The essay Don’t Use VPN Services accurately captures my feelings about what VPN services really offer and whether people should use services that they don’t control. ↩