Reserve Bank of India's Interventions to maintain excess liquidity - Part 1

11 Jan 2021 central-banks · economic-theory · economy · governments · indiaIn December 2020, I came across several articles about India’s Central Bank, the Reserve Bank of India, intervening in the open market to maintain excess liquidity of the Indian Rupee in the market. With my elementary understanding of currencies, I understood that this excess liquidity of INR in the market, would keep the currency weak against other currencies, and this seemed undesirable. In this post and the next one, I will delve into the complicated reasoning behind the RBI’s choices and their delicate balancing act which seems to be associated with a high but manageable amount of risk.

Premise

Last month, I came across several articles that were talking about the same kind of topics:

- Huge outflows from India’s bond markets (bloomberg.com, theprint.in)

- RBI’s aggresive buying of the USD flowing into Indian equity markets (bloomberg.com (1), bloomberg.com (2), moneycontrol.com)

- RBI’s growing policy woes and their potential lose of control of the INR (Indian Rupee) (msn.com, bloomberg.com)

- INR’s momentary appreciation, after the addition of India to a Currency manipulators watchlist by the US, which lead the RBI to reduce it’s aggressive buying (finance.yahoo.com)

These topics are all closely connected to each other. In fact, they are all so closely connected that reading these articles a couple times left me very confused about what was going on, what the RBI was doing and why the RBI was intervening into a market that wanted to increase the value of the INR. I will cover the first two points in this post; and a future post will cover the last one.

What’s going on? (before RBI interventions)

There are a few inter-connected things that are happening simultaneously. (This is a subset of all the things that are happening in the economy)

Significant drop in the Inflation-adjusted 10-year Indian Government bond yields

Over the 9-month period from Jan-Sep 2020, outflows from the bond markets totaled up to $14bn. In comparison, the investment in China’s bond market amounted to about $120bn. This exodus could be fueled by the low levels of inflation-adjusted bond yields: The bond yield hovers around 6%, whereas the inflation number is hovering around 6.8% to 7.6%. While this inflation-adjusted number might not deter domestic investors, for foreign investors, this negative inflation-adjusted bond yield number makes it hard to justify investment in the Indian bond market. Although, it looks like the outlook for 2021 is optimistic:

“We are constructive on the Indian market next year as India is a high beta market in EM,” said Emily Alejos, chief investment officer at Cartica Management in Washington D.C. “We expect all EM to prosper.” – msn.com

Another thing to look forward to is the inclusion of the Indian 10-year benchmark bond in global indexes, which will automatically bring inflows through Index funds.

Huge capital inflows into the Indian equities market

On the flip-side, capital has flown into the Indian equities market. For the past, this can be seen in the increase of the main index, the NIFTY50 which went from 12,182 points to 13,981 points, an increase of 14.76%. One-year forward earnings are about 28 times according to the msn.com article, and this has pushed cumulative Foreign buying of Indian equities to about $20bn, from 1st Jan to 15th Dec 2020. This is the highest since 2012 and has caused an unprecedented build-up of USD with state banks.

The outlook for this continues to be very strong with most analysts expecting this rally in the investment into Indian equities to hold atleast until Dec 2021. The Indian economy’s recovery has been sluggish so far, but with the widespread inoculation of vaccines and a reboot of economic activity and engagement to 90+% of pre-Covid levels, foreign investment might even go up further.

(As we will see in the second post of this series, this increase in foreign inflows causes a risk of “Over-valuation” of the rupee and RBI has been fighting back using aggresive USD purchases)

Supply-side shocks raising all Inflation numbers (caused by COVID-19)

As the COVID-19 pandemic started spreading in India, the government acted swiftly (to a fault and perhaps prematurely) and imposed a nationwide lockdown. This lead to a breakdown of most supply chains as long-distance trains stopped operations and all state borders were effectively closed. There was a push to ensure that the supply of essential goods and truckers would remain unaffected, but this didn’t work well enough and the bureaucratic system to grant permits to truckers most probably took more time than the government initially anticipated.

This sudden supply-side shock had an expected impact on the CPI Inflation across the country. Food inflation started shooting up from April, but the expectation of a good harvest kept fears low initially. As October rolled around, untimely rains in Maharashtra (a major farming state) lead to the food inflation going up to 11.07%, an all-time high for this number. Overall inflation also kept going up, and ended up at around 7.6% by early December.

The key finding here is that this inflation is not connected to any of RBI’s monetary policies. In fact, according RBI’s assessment, they confidently claim that the effect of their currency interventions on inflation have been minimal:

Statement by Dr. Ashima Goyal

Point 43:

To the extent it is transient the contribution of excess liquidity to cost push inflation is limited. In an open economy import competition also caps price rise, especially with a rupee that is tending to appreciate, provided tariffs and taxes are moderated.

– https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=50831

Note: For this series, I will take the RBI Monetary Policy Committee members at face value. In this regard, healthy skepticism is appropriate, and I will write more about this if I go out to find something critical about the RBI’s monetary policy.

Rupee’s weak recovery from the initial recession (caused by COVID-19)

Once again, moneycontrol.com and the INR/USD spot rate chart both show that the exchange rate was kept in a tight window up to July; the INR/USD ratio stayed above 74.7 from 20th Mar to 21st Aug 2020. The currency’s appreciation was allowed for a short period of 10 days from 21st Aug to 31st Aug, when it dipped to 73.12. After this short hiatus, the RBI restarted it’s intervention to support the INR/USD ratio at or above 73.5, and not allowing the INR to appreciate below this number (Note: A decrease in the INR/USD ratio is considered an INR appreciation).

Across all Asian currencies, INR’s initial depreciation was the highest. After September, INR’s appreciation was the smallest as shown in this chart. One should note that the prevention of appreciation of the INR after Sept, and the prevention of momentary depreciation after some border skirmishes were both direct results of RBI’s intervention. This intervention was egregious enough to get India added back to a Currency manipulation watch-list by the US.

(As India waits to be added to global bond indexes, one of RBI’s goal seems to have been to curtail volatility in the exchange rate by keeping it within a tight window. India’s bonds have not been included in global indexes mainly due to an overly restrictive regulatory framework, which has not been modernized quickly enough)

What is the RBI up-to?

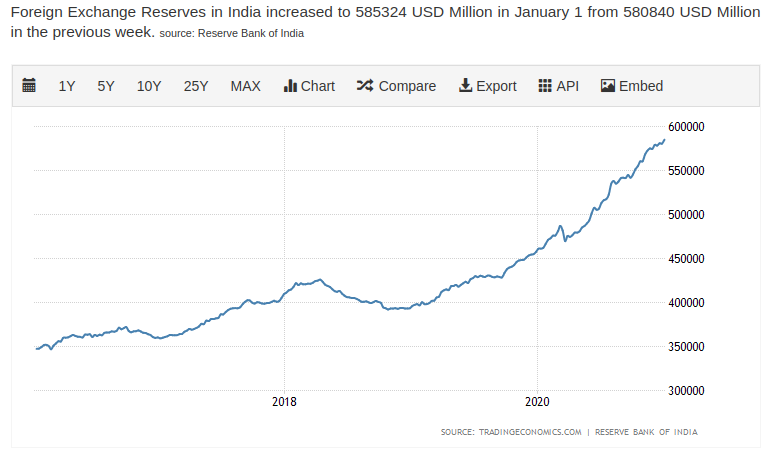

This graph of the RBI’s foreign exchange reserves tells the whole story. IT shows the foreign exchange reserves going up from $450bn at the beginning of 2020 to almost $580bn at the end of 2020.

The actual numbers can also be found in the RBI’s Weekly Statistical Supplement

Sidenote: This page on the RBI website has become my favorite page to get macro information about RBI’s activities. RBI also maintains this, the Database on Indian Economy, but I have not been able to figure out how to download an spreadsheet of time series data or use the native “Filter” feature yet.

| Date | Value | Year-on-Year increase | Supplement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-01-05 | 385103.9 | 14.415901 | 2017, 2018 |

| 2019-01-04 | 368077.2 | -4.4213263 | Link |

| 2020-01-03 | 424936 | 15.447520 | Link |

| 2021-01-01 | 537474 | 26.483518 | Link |

(Value is the amount of Foreign exchange reserves held by RBI in millions of US$)

The 26% increase in reserves from the previous year is stunning. This has also pushed RBI to the fifth place in the list of central banks with the largest reserves of USD.

This purchase of USD, offsets the increase in the capital inflows. The inflows into the Indian equity market were $20bn, whereas RBI has purchased nearly $113bn in USD in the same amount of time. This asymmetric intervention has helped them flood the market with excess INR liquidity and effectively prevent the INR from appreciating against the dollar. It was only after RBI was added back to a currency manipulators watchlist did the INR appreciate in real terms. This appreciation was short-lived and the RBI got right back into USD purchases. They continue to make weekly purchases and increase their reserve foreign exchange reserves. Why is the RBI involved in preventing the appreciation of the Indian Rupee? I will try to present a few advantages and disadvantages of the RBI strategy in the next blog post (to be released tomorrow, 2021-01-11).