More Access Leads to Better Governance

28 Jun 2021 democracy · governmentsHere’s the noble lie about democracy: The electorate holds the ruling party accountable for their actions during the next election. This is taught in classrooms and in political science courses; it is drilled into the minds of children who have the good fortune of growing up in a liberal democracy. The truth is revealed when they realize that the electorate is unwilling or unable to hold the ruling party accountable and that the ruling party is able to entice the electorate with populist schemes that are announced hours before campaigning begins1. There is a tedious and disheartening conversation about why no country has realized this ideal state of democracy in practice or been able to stay in that state for a long period of time; a conversation that would identify the media, political self-interest and capitalism as a few of the causes. This post does not engage in that conversation. Instead, I focus on a core component of this system which would hold the noble lie up: Access to public services such as education, healthcare, and a competent local government. I contend that widening access is the silver bullet which will allow countries to reach the ideal state of democracy and maintain that state in the long term.

The Noble Lie

Let’s look at the lie in some more detail:

- The electorate votes for a political party every few years

- The elected political party forms a government and works for the welfare of a majority of the people

- When the next election comes along, the political party campaigns on their credentials. Namely, the changes they brought about in society during their term in office and their plan for the future, as documented in their election manifesto

- The electorate hears all this rhetoric and looks objectively at the government’s performance

- At the voting booth, the electorate holds the government accountable for their actions during their past term, by voting for either the same party, signaling that they did a good job, or for the opposition party, signaling that they did not live up to the electorate’s expectations

- If the ruling party loses, then they go back to the drawing board and await the next election

- Whichever party lost the election will become the new opposition and will keep a close eye on what the government does. They will find counter-arguments to every policy that the ruling party puts forth, and this is an important part of the electorate’s opinion forming process

GOTOStep (1)

At least one of the above steps is broken in all of today’s liberal democracies2.

Step (2) has never really worked. The government is focused on winning the next election and does what will work out best for their current and potential supporters; not bothering too much with the ardent supporters of the opposition party. The stickiness of political ideologies supports this approach. If one were to assume a utilitarian point-of-view, the limited resources that the government has access to must be used to safeguard their path to office in future election cycles. There have been a handful of astonishingly selfless politicians, such as those inside the conservative party in Australia who implemented gun control at the cost of their political futures following a mass shooting. These politicians are the exceptions that prove the rule.

Step (4) is universally broken. The electorate learns about what the government has done through the media and the media is regulated by the government. This is a conflict of interest for the government. Media organizations have their own ideal state which they have not achieved and the failure to live up to the requirements of step (4) are the result of knock-on effects of dependent systems, each of which is far from its ideal state. I have written about this problem before.

Step (5) is broken in countries where the government has expansive, unchecked powers over spending. In effect, the government is empowered to bribe the median voter through populist schemes. The government can thus side-step the requirement of “performing” when in office, but still convince voters on the campaign trail. There are also out-of-band methods3 like “Cash for votes” schemes to convince voters, though owing to their nature these are less frequently documented.

Step (6) is hard to adhere to for an enterprising political party. The ruling party is unwilling to reevaluate their policy platform or the changing demography of a country following an election loss. This refusal to change has lead to endless shouting matches on nightly news shows and walk-outs from legislative bodies that accomplish absolutely nothing in the Parliamentary system of governance that exists in India and Britain. It’s utility is questionable in separation-of-powers democracies like America. In an astonishing example from America, the losing side embarked on a national campaign to disenfranchise supporters of the winning side in early 2021.

Here, I will end this inventory of the failures of democracy and move on to my core argument.

What is “Access”? What are it’s Determinants?

“Access” is an ambiguous concept and risks becoming a catch-all term. I will define it concretely for our purposes here:

Access is the availability of public services like education, healthcare and a competent local government. These are things that private individuals can not do as efficiently as the government. Apart from these enumerated facets of access, we should consider pensions for the elderly, rations for the poor, opportunities for the unemployed and public transport for all as essential public services.

I think there are two determinants of how much access someone has during their formative years.

First, Access is heavily impacted by geographical location, with people in urban areas generally having better access due to the higher per-capita government revenue and the government’s enhanced ability to recruit talent willing to inhabit these areas. People in rural areas generally have little or no access to essential services and are often compelled to go considerable distances to procure them. Anecdotes about Indians walking several kilometers every day to go to school or college are commonplace even as recently as the 1990s or 2000s.

Second, Access is determined by socioeconomic position. The wealthy landowner in a rural area has the ability to shuttle their children to school or move closer to the school for a period of time, while everyone else is left behind. Further gradations become visible as children move to higher levels of education; the entrance exams for several Engineering colleges in India are held only in English and Hindi4, creating a major barrier for students who studied in schools where a regional language was the medium of teaching.

This difference within members of the electorate profoundly impacts what they do as participants in the democratic system.

Why is Access Important?

To understand the importance of access, I will break the election process into three separate stages: the pre-election stage of electoral polls and campaigning, the voting stage, and the post-election stage of measuring government performance.

Before the election: Polling and Campaigning

The impacts of access at this stage are under-discussed. Political parties use private and public polling5 to gauge what the electorate wants to hear them talk about. Who gets polled depends on how much access they have. The most common method for polling in America is calling people up on telephones. Someone who does not have a telephone is not likely to be polled and their opinion remains unheard by political parties before the election.

In smaller economies and middle-income countries, the problem becomes even bigger. Internet penetration in India is about 45% which reduces the utility of online polls like this one.

Looking at traditional polls like India Today’s Mood of the Nation 2020 poll, we notice the difference between the country’s literacy rate and the literacy rate of the people who were polled; while about 75% of the people in India were literate in 2018, about 96% of the people polled were literate. This gap makes the poll less representative because only 1 out of 5 illiterate people in India got the opportunity to voice their opinion. The poll’s coverage of the whole country is also spotty with only 97 of the 543 Lok Sabha constituencies surveyed. This poll is decidedly not the mood of the nation. Rather, it’s the mood of the people within the nation who have the most amount of access6.

Campaigning is less of a problem related to access because political parties campaign in places where there are persuadable voters. These places are generally chosen irrespective of the amount of access they have. A politician will travel as far as they need to if they can get an audience with a few thousand persuadable voters.

So, if you (or counterparts in your cohort) are not being polled routinely and diligently, then your options for getting your opinions to politicians are limited. One potent option which is widely recommended is to “get involved in local and regional politics” and talk to the politicians who are closest to you and explain your concerns to them. Each democracy provides it’s own method of accomplishing this.

America provides the public forum and town council meetings, whose inefficiency and ineffectiveness was immortalized by the excellent TV show, Parks and Recreation. Decentralized democracy generally provides multiple levels of politicians starting from a local counselor or panchayat leader (in towns and villages in India) going up to a member of the state or federal legislature. I think that this option is mostly touted for show. People at these levels are impossible to find, meet or talk to. Their functionaries are equally powerful and (generally) just as absent. Above all, this assumes that the duty of a citizen extends well beyond voting in an election: If they want to get their opinions out, they have to find someone who can effect change and proactively tell them about it. This seems like a dream and is not backed by anything that exists in reality. This ability to be proactive is again dictated by socioeconomic situation, with people who are well above the poverty line with more flexibility at their workplace to take time off and meet with the people who matter7.

There are some caveats to my opposition to this idea. The implementation of democracy has varying levels of imperfection across the world. Thus, theoretically, it is possible that a democracy somewhere in the world has really good processes which allow the voice of everyone to be heard. At scale, I don’t think that expecting citizens to be proactive is acceptable. Incentivising the government and political parties to employ private companies who do surveys and weight the results appropriately to represent the whole country sounds like a much better option to me.

During the election: Voting booth

Access to the voting booth is an important part of democracy that democracies generally do better at. There are few complaints about these. While citizens might struggle to get their voices heard before an election, when an election comes around, politicians would generally like to lock down the reliable voters who will vote for them and will be in favor of policies that bring them into the fold.

I will offer one minor and one major instance where access to the voting booth is systematically limited.

The minor caveat comes from India. India runs the world’s biggest election every 5 years. In 20198, 910 million people were eligible to vote, while 610 million people actually voted, resulting in a polling percentage of 67%. These votes were cast over 5 weeks to elect 543 Members of Parliament. These numbers are staggering. The polling percentage in particular is comparable to American turnout during the 2020 Presidential election, an older democracy which has several features for convenient voting such as early voting, mail-in ballots, and same-day registration, which are missing from the Indian election process.

The lack of these convenience features makes it nearly impossible for someone who isn’t close to their assigned voting booth in an election. For anyone to vote in an Indian election, they must be registered to vote and have a voting slip. The voting slip specifies the polling booth that has been assigned and one is required to present oneself at the polling booth, on the assigned day, between 9 am and 5 pm (or a similar time period). This geographical restriction is an annoyance and creates a bias towards people who stay in the same place for a long time. In an economy that is still largely agrarian, these concerns are inconsequential9.

The major instance of systemic denial of access to the voting booth emanates from the politician’s desire to empower reliable voters who will vote for their party, while simultaneously finding dubious methods to disenfranchise reliable voters of the opposition party. There are two ways to deal with reliable opposition voters: persuade them that one’s party will product better outcomes for them or exclude them from the electorate.

There is really nothing more to say about this; if democracy is about convincing the electorate to vote for you and you are in charge of including and excluding people from the electorate, it makes complete sense to prevent the people who will not vote for you from being a part of the electorate. The Republican party in the American South decidedly went over the cliff on this in early 2021 and wholeheartedly committed to disenfranchise a large block of voters who turned out for the opposition in the previous election; their policies have been outrageous and they have not bothered to even present these policies in a palatable form. This kind of disenfranchisement was going on in the form of Gerrymandering, the American process of periodically redrawing districts to bunch up one’s own supporters into reliable constituencies, while breaking up the opposition’s supporters into multiple districts ensuring their inability to forge a plurality anywhere. While that was an obscure form of distorting the electorate’s powers, preventing Sunday voting is a direct and indefensible form of exclusion.

Similar legislative policies were nearing implementation and were widely protested in December 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the government to apply the brakes and focus on a separate crisis. The Indian government’s determination to implement the various citizenship tests and registers appears to be undaunted and with 3 years remaining in their current term, it seems entirely possible that they will implement at least a part of the agenda that they left unfinished before the next election in 2024.

After the election: Measuring government performance

Approval ratings are calculated using surveys that ask people some form of a straightforward question: “Do you approve of the current government’s performance?”. By keeping the question simple, they aim to capture the public’s approval of the job that a government is doing, implicitly assuming that the public will take into consideration all the various things happening in the country. It is a purposefully coarse metric which tells people about the present. It is not very helpful in the long run, except for direct comparisons between different leaders (even in comparison, the usage of approval numbers is suspect because of the differing conditions that a leader has to deal with when they come into office).

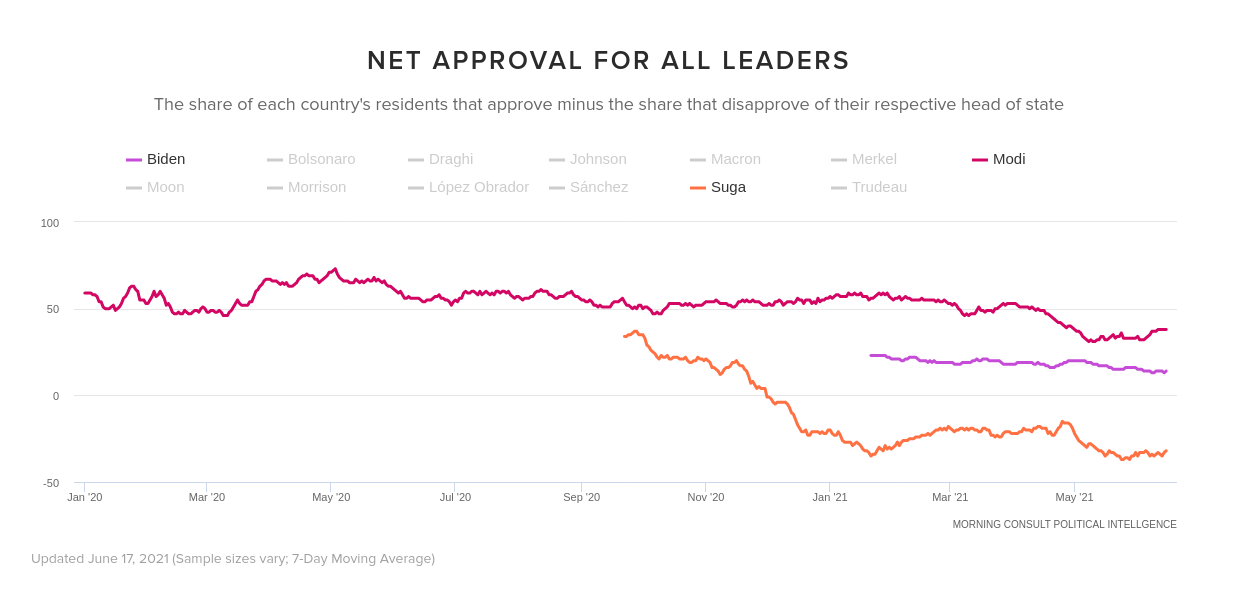

Morning Consult’s weekly poll gives us some idea of the approval ratings for leaders around the world.

The methodology of the survey determines the final number and different numbers can be found for America on FiveThirtyEight’s approval poll average and for Japan on NHK, the state broadcaster’s monthly survey of about 2000 people.

These numbers can be easily goosed and have wide short-term variations. For instance, when Modi, the Prime Minister of India, announced a nationwide lockdown to contain the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the 7-day moving average of his net approval shot up from 52% on March 21st (3 days before the announcement) to 63% on March 27th (3 days after the announcement). This increase is not meaningful, as the effects of the lockdown were not visible in that short period. When the disastrous effects of the lockdown became apparent, the net approval returned to it’s original level around 53% in June 2020, nearly 3 months after the initial announcement.

Measuring the Government’s performance is a tricky task for any citizen. Access plays a pivotal role in this; specifically, the citizen’s access to information, their ability to process this information, and their ability to come to an independent conclusion (free of peer pressure and intimidation). All these facets of access are determined by the amenities available in her neighborhood in the present and the opportunities she was able to avail in childhood. People who are illiterate or physically challenged have been systemically excluded from the information ecosystem, although the advent of accessibility tools such as screen readers and platforms such as YouTube with content in several regional languages is gradually filling this access gap. We should be cautious in becoming too optimistic though as access to the Internet is far from perfect, even in some advanced economics.

Free and good quality primary and secondary education is also facing several obstacles and on this front, there is a wide gap between various countries. When one looks at the amount of time that schools and other educational institutions were asked to stop functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic, I think one can gauge a government’s attitude towards the education of their citizens. While schools remained closed in America and India for several months, Japan and France rushed to open their schools as soon as the first waves of the pandemic ended and doctors were able to understand the disease better.

As evidence mounted showing that the spread of the disease in schools is limited and can be curtailed using common-sense measures such as masks and social distancing, some countries responded by implementing these measures and reopening schools, while others decided to forget about them due to upcoming elections. The Indian government went one step further and canceled the year-end exams for CBSE, a nationwide education board, impacting 15 million students who were to take these exams in April 2021. The exams were canceled without any clues about what their replacements will look like and the whole thing was a huge communication failure which left a lot of students anxious about both the near- and long-term.

These decisions were made at different points during the pandemic and support for them is divided among the electorate. I don’t know of any poll that has asked people about their opinions on how important it is to open restaurants and movie theaters compared to opening schools. The Economic Survey in 2020 found10 the drop-out rate in secondary education in India (age 10 to 17) to be about 19.89%. This number is bound to have increased during the pandemic. It is a near certainty that the past year of school closures will increase social inequality in the coming decades.

-

This is probably a pessimistic view, an overstatement and a simplification of the nuanced reality. But the inaccuracy of this statement is well within the tolerances that I have set myself for evaluating the performance of a democracy. ↩

-

For this post, I consider polling to be the systematic science of calling up probable voters and asking them questions, in order to gauge the public’s opinion on social, political and economic issues. ↩

-

I have made some assumptions here. Namely, I have assumed that this poll covers the easiest places to survey: urban and semi-urban places where access to telephony is high and people are reachable by various modes of communication. The names or economic attributes (such as the median income of the polled constituencies) of the 97 constituencies that were polled are not available in the “Methodology” section of the poll. Given this lack of information, I have decided to not give the benefit of the doubt to the polling agency, because they have not explained their weighting of the survey results or whether they have employed statistical processes to deal with minor inaccuracies in surveys or the differences between the sample’s population and the country’s population. ↩

-

Shanghai (2012), an Indian movie, is a good reference for learning more about how the bureaucracy works in India. The New York Times podcast series, Nice White Parents, is a good example of how a motivated group of people, with a lot of time and willingness on their hands, can bend the system’s rules to favor themselves and their group. A deeper discussion of both these works will not fit in this (already quite long) post, and I decided to drop them and focus on the core argument here. ↩

-

Highlight Statistics from the 2019 General Election in India ↩

-

In a hilarious turn of events, a successful movie in 2018 showed the protagonist, loosely based on Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai, coming back to India to cast his vote and the drama that ensues when he realizes that someone else has illegally voted on his behalf. ↩

-

Statistical Appendix to the Economic Survey of India 2020-21. See p. 173. ↩