Book Review: Global Economic History (Allen)

29 Jul 2022 development · economics · historyAllen’s Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction is a 200-page masterpiece. It packs a huge amount of history. It looks far enough into the past to set the scene for the Industrial Revolution and the economic gains seen as a result of it. Then, Allen retreats into the fundamentals of economic development and goes over the main reasons some countries are perennially stuck in the “middle income trap.” He has some advice for such economies and what they might be able to do to get out of this trap. This book is solidly based in data. But Allen does not prioritize data over the story. Economics is the story of real people who live in each of these countries. Allen never loses sight of this, and always puts large economic shifts in context by stressing on how it impacts everyday life. This emphasis on personal experience makes the book a study in the government policies that work and the pitfalls to keep in mind.

The topics is quite deep and consequently, this post is long. I have categorized it into multiple sections for the reader’s convenience.

- Introduction: I start with an introduction of the world economy and the large shifts that have been seen over the past few centuries

- Standard model for economic development and the industrial revolution in Britain: In modern times, this remains the largest fundamental change in the way people worked and the way their lives were organized, with people moving from villages to cities and leaving farming for industries

- 4 topics related to middle-income economies

- The middle-income trap

- Why literacy must be perceived as useful for people to send their children to school

- How imported technologies and their adaptation is essential for economic development

- The big-push industrialization model for economic development

- Africa’s woes: Finally, I talk (briefly) about the African region’s woes and some reasons for the lack of development in that region since 1820, and why it remains the poorest region on the planet.

Introduction

The economic history of the whole world is a nearly intractable subject. Allen begins with a table that shows the difference between the present and the past.

| Region | GDP per capita in 18201 | GDP per capita in 20081 | Multiplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK | 1,706 | 23,742 | 13.91 |

| US | 1,202 | 30,152 | 25.08 |

| Japan | 669 | 22,816 | 34.10 |

| World | 666 | 7,614 | 11.43 |

| China | 600 | 6,725 | 11.20 |

| India | 533 | 2,698 | 5.061 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 415 | 1,387 | 3.34 |

The countries that were rich in 1820 continue to be the richest of the lot. Nothing surprising there, those countries had a head start. Sub-Saharan Africa is the region that has grown the least in the intervening 2 centuries. But the numbers look encouraging, right? Allen dives into the details of what these numbers mean and what one should take away from the development paths that these economies have taken.

Over the past few centuries, the trajectory is easier to visualize. Between 1500 and 1800, European powers discovered many regions on the planet and colonized those regions. Most of the trade in the world was done by colonial powers who imported products produced in their colonies. In 1750, China and India dominated world production with a 33% and 24% share of the total production respectively.

After industrialization kicked off in Britain, products were produced in Britain and exported to the world. These products were much cheaper than those manufactured in the colonies (such as cloth from China and India compared to the cloth made in Britain, using the cotton mill.) As the cheaper products took over market share from China and India, Britain’s economy strengthened at the cost of China and India’s development. Until the 1990s, their share of global production kept declining.

The colonisers had another advantage: Not only did they produce cheap goods using modern technology, they also controlled the prices of competing goods. So, Britain could take a commodity like salt, which can be cheaply produced in India, and use import tariffs to ensure that salt imported from Britain is cheaper than salt produced in India. This diabolical use of colonial power was the reason for the “head-start” which colonial powers gained. They were able to destroy their competition and they could compel their customers to buy from them.

In India, after independence, from 1947 until Liberalization efforts in 1991, the economy struggled to grow. China was stuck under Mao’s disastrous implementation of communism which lead to the death of millions. Starting in the late 1980s, China started catching up very quickly. Indeed, most of the world’s improvement in the 4 decades between 1980 and 2020 can be attributed only to China’s growth. India was never able to capitalize on this trend of East Asia’s economic strengthening in the 21st Century, and thus, was never able to recover from the colonial collapse.

Looking into the future, it is clear that China will soon overthrow the US as the largest economy in the world. When that happens, the world would have come full-circle. (India would have missed the bus to make this cycle work and will be stuck in the middle income trap.)

Why did the Industrial Revolution happen in Britain, and not in India or China or Germany? This is the key question of economic development. Allen tries his best to convince us that geography and access to resources was the driving force of the answer.

Standard Model of Economic Development

The standard model of economic development was followed by US, UK, Japan, and partly, by the USSR. The idea is that a country can not advance itself by only exporting surplus agricultural produce, so it should take steps to ensure that it has comparative advantage on some products. It should import what can not be produced cheaply locally and it should export what can not be produced at a lower cost elsewhere. To produce more and more things locally and at a discount to its global rate and shipping cost, it should import technologies from more advanced economies and protect businesses in their early stage until these businesses can learn to innovate on the imported technology and improve them.

- To go from being a primarily agrarian economy to a primarily industrial one, countries will generally start with cheap capital. There is a need for a banking system which will invest in development inside the country.

- This capital is then used to build the requisite infrastructure around the country: roads and railways. During the building of this essential infrastructure, the country will develop local industries for manufacturing of materials such as steel and the operational knowledge for running railways, etc.

- As the infrastructure is coming up, countries will incentivize the creation of new businesses and the manufacturing of more and more things domestically. During this period, the products that are manufactured domestically will be inferior and expensive compared to the “state-of-the-art” elsewhere. However, governments must implement import tariffs to ensure that imported goods do not compete with domestically produced goods. The only way to foster industry in the early days is by protecting it from competition.

- As industries inside the country find their footing with manufacturing and are able to import technologies and adapt them to local settings, they will figure out cheaper ways to produce what was being imported from other countries. This will increase the competitiveness of their products abroad and the economy will enter a virtuous cycle of innovation and competitive production.

This standard model worked very well for Britain, because it had cheap capital and cheap coal.

The model worked for the rest of Northern Europe as well. Their proximity to Britain and their colonies bolstered their ability to catch up to the fast industrializing Britain. Some European economies were even able to overtake the British economy in the industrialization race.

It worked very well for the other independent economies that were trying to develop during the time of Empires: The US was able to keep British goods out by implementing tariffs. The US also had practically free land, as the British colonies on the East Coast started expanding into the Wild West.

It worked well for Japan: Japan had cheap capital and the ability to adapt technologies which were imported from the West to fit local restrictions.

However, this model did not work for the colonies. As it is, colonizers do not want colonies to develop too much. Colonizers will produce many things cheaply in their own countries and start pushing them into the colony. This prevents businesses in the colony (if these are allowed to exist) from ever having the protective environment that is required to start producing.

In the case of building infrastructure, again, the colony is seen merely as a market for the colonizer’s goods and nothing is manufactured locally. In The Great Hedge of India (Moxham), Moxham demonstrates how the British deviously used tariffs to ensure that salt produced in India would be sold at the same rate as salt imported from Britain. When railroads were laid in India, nearly 61,000 km of railway tracks were laid by the British using British steel. India was never able to develop her muscles in the large-scale manufacturing industry, which is a requisite for entering the next stage of economic development. This is the reason the standard model never worked for colonies and they had to start from scratch when they became independent.

Things got much worse after World War 2. The standard model stopped working. The global banking system had become too interconnected for capital to be invested in new economies and be cheaper relative to the cheap labor that was available in these economies. Some misguided protectionism after the war lead to stagnation and an utter lack of accumulation of knowledge or skills in the developing economies. When the economy was opened up after this period of protectionism, countries realized that they were forced to import most products that they needed due to the principle of comparative advantage. All of this culminated in the stagnation that Allen calls the “Middle Income Trap.”

Large institutions like the IMF, World Bank, European Union have made institutions in African countries which have not paid off because these institutions want to push the “free market” idea into small, maturing economies. Only large economies such as India and China were able to ignore World Bank advice, while economies like Pakistan and Sri Lanka had to follow this advice, and now, their economies are on the brink of collapse. This is covered in Reinhart’s “This Time Is Different.”

The standard model also relies on the Minimum Efficient Size (MES) of innovations. For every innovation, it is worth investing in the innovation only if the factory that uses it produces at the MES. When Latin America tried to apply the standard model in 1980, the MES of state-of-the-art innovations had skyrocketed. A single factory of MES size would be enough to serve all the domestic demand. This stifled the need for innovation and a monopoly was an efficient solution in this situation. But a monopoly does not foster innovation or competition, and is bad for a country’s economy.

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial revolution in Britain was a key turning point for the West. They had already gone from being mere monarchies to colonizers; but industrialization gave them the incentive to double down on colonization and squeeze colonies of any chance of development. Cheap coal, cheap capital, and high wages came together to make Britain the center of the Industrial Revolution.

The prohibitively high cost of labor and the relatively cheap cost of capital pushed research forward in several domains and Britain ended up improving the production process of many goods. The leading producers of these goods were often countries that Britain had already colonized, so they were able to squeeze the colonies from both ends: reducing production in the colonies through British brawn, while improving production processes at home through British brain.

Allen goes through an impressive list of innovations which all came out of Britain during this period. While the list may be impressive in itself, it should always be kept in mind that colonization and the attendant atrocities were the prerequisites for these innovations.

- Cotton: Chinese and Indian cotton was surprisingly competitive in Britain, even as late as the 1770s. And in West Africa, British cotton was far too expensive. The spinning jenny and the mule made sense in Britain’s high wage environment. They gave a total return of 40% when employed in Britain. Whereas in France, the return was 9% and in India, it was a meager 1%. So, India saw no mechanization of cotton spinning. As the installation of these machines kick-started future improvements in cotton spinning, the setback faced in this period was of colossal proportions for India and other countries where labor was cheap.

- Power Looms: Wages in America had surpassed Britain in the early 1830s. So, as expected, Power looms were embraced with much more gusto in America than across the Atlantic.

-

Steam Engine: The initial coal requirements for introducing a steam engine were very high. In the cheap coal environment in Britain, this was not a problem at all. Research continued steadily and significant improvements were made. In 1730, Newcomen engines required 20 kgs of coal2 to generate 1 horsepower of energy. By the late 1800s, this number had gone down by a factor of 40 to 0.5 kgs of coal.3 British innovators cut through the technological frontier because they were the only ones who had access to the high initial requirements of coal. If countries could not clear this initial barrier, they would be forced to import technology from Britain at a premium. (This is what Japan did when railways were introduced in

- British engineers are credited in Japanese railway museums with installing the first tracks

and trains.)

- Railways: Starting in 1830, the power of Steam engines was successfully applied to locomotives which ran on iron rails. The network grew around Britain very quickly, increasing to 10,000 km in 1850 and to 25,000 km in 1880. The locomotive was popular among passengers who wanted to avoid bad, unpaved roads for long-distance travel. It was also a popular mode of transport for general freight.

- Ships: The Steam engine transformed shipping. The sail lost ground and steam took over, with ships carrying the coal required to power their Steam engines. Initially, the space required to store the coal required for a cross-Atlantic journey was too high. However, as the weight of coal required per horsepower plummeted, the steam engine became the most common way for powering Atlantic crossings.

While England had the first-mover advantage in the Industrial Revolution, the rest of the continent caught up to Britain by the 1870s. Indeed, Germany and France had surpassed England in cheap steel production.

Strikingly, during this furious period of innovation between 1770 and 1870, there were no major inventions anywhere else in the world.

Escaping the Middle Income Trap

Some countries are stuck in the “middle income trap.” A part of their population is always in abject poverty and the doors of social mobility are permanently closed to them. Why do some countries get stuck in this trap?

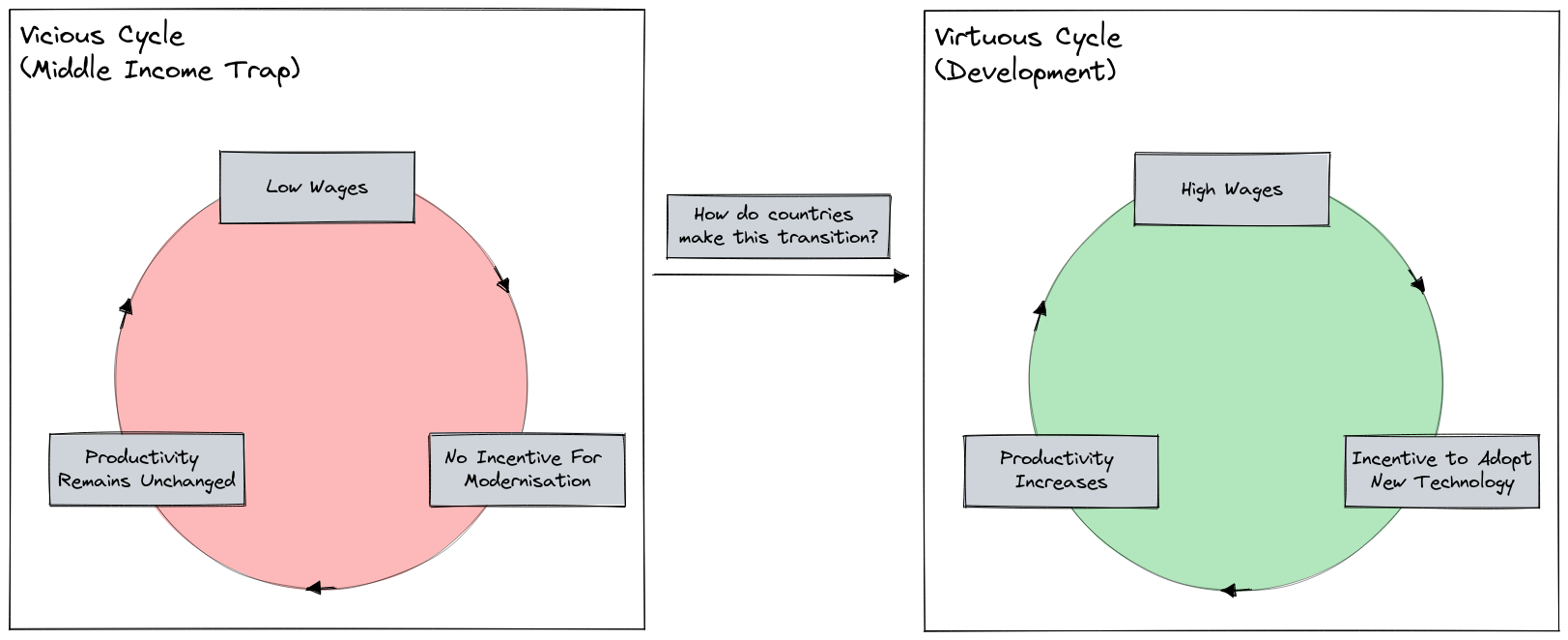

Every country starts out with no real technology. They use the tools that have been used since antiquity for the first part of their development. During this period, wages are low and businesses have no incentive to invest in technology which will increase the productivity of each worker.

As the productivity does not rise, the total amount of product produced by the country does not rise either4; and the country is stuck in a trap. There is no “natural” way for an economy to get out of this trap. The market is running efficiently by not innovating. There must be an external stimulus to go from the “Vicious Cycle” to the “Virtuous Cycle” in the diagram above.

There are a few different paths that Allen describes. For each path, Allen describes a case where it was successful in the past.

- The first strategy is the most common method to get out of this trap. Some countries increase workers’ wages. This creates incentive for business leaders to squeeze more product out of the workers’ (now limited) time at work. This incentive will turn into innovative technologies which are either invented or imported. This worked well in England where machines to spin raw cotton into yarn kick started Industrialization.

- The second strategy is government investment. The government invests a huge amount of money in

businesses and forces them to modernize their infrastructure. This strategy was most effectively

used in recent years by China. The question remains, where should this money come from? For rich

European countries, this meant digging into their, coffers which had gotten rich through the

exploitation of their colonies. For poor countries or countries which did not colonize anyone, it

meant taking loans from foreign investors. There is a pitfall here though. When a country is

large enough and the central government is powerful enough to stamp out (unreasonable amounts of)

corruption and internal strife, foreign investors never gain enough power to exploit the

country. However, if the country is corruptible or its economy too small to make much of a dent,

it is ripe for exploitation by its debtors. Foreign debtors are greedy and can often push the

country into unwanted spirals of debt restructuring to the debtors’ benefit. So, being in debt

can be a dangerous strategy for some. The infuriating story of France’ exploitative arrangements

with Haiti in order to collect the independence

debtransom is a classic example of an economy which was exploited by its debtors. - The final strategy is brute-force improvement of productivity through increased work hours and technological adaption. The adaption of imported technologies is important for economic growth and there are many instances in the past where it is clear that countries that can adapt imported technologies fair better than those which import technologies and try to use them as is, without redesigning them for local economic conditions. Asian economies which flourished and reached the top of the world economy after World War 2 are prime examples of this technique: Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Incentives to Become Literate

Literacy is good. It informs the population, enables them to choose better leaders (until recently, at least), and increases the opportunities that ordinary citizens get. In the TV show Downton Abbey, an undercook learns mathematics and history from a local school teacher. Soon after, we see that her confidence increases and she feels comfortable saying out loud that she does not have to be an undercook all her life. This is the character of social mobility: If you want to convince a majority of your population that becoming literate is good for them, then they must see the benefits first hand.

Northern Europe saw significant increases of literacy by the 19th century. Most of these increases were powered by the imperialism that had become essential for most European nations. As imperialism advanced, these countries became rich and products that were imported from China were soon produced cheaply at home due to industrialization. The demand for these cheap products went up and wages increased as people saw that there was use for their money.

As wages increased, parents sent their children to school and children studied as they could clearly see that educated people had better opportunities in a fast industrializing world.

| Country | Literacy in 1500 | Literacy in 1800 |

|---|---|---|

| England | 6% | 53% |

| Germany | 6% | 35% |

| France | 7% | 37% |

| Italy | 9% | 22% |

| Spain | 9% | 20% |

Efforts were taken to keep children in school because the economy demanded literate participants. For e.g., in the American settlement, literacy was a considerable advantage after America’s independence in 1776. State schooling and mandatory attendance were introduced in America almost immediately after independence, and trade with Europe continued unhindered. Children went to school and literacy spread because it was economically advantageous. On the other hand, in Mexico, only 20% of the population, almost all of the White men, were literate. The remaining population, mostly non-White peasants, did not see any economic advantage to becoming literate. This held them back. While the highly literate men in America had access to journals and magazines about increasing crop yield, the peasants in Mexico slogged away using methods that had been used by their forefathers. (Due to the nature of colonization, even if there had been a demand for universal education, it would most certainly not have been provided by the ruling class.)

The main takeaway for me was that it is important to *convince the population that the benefits that literacy will accrue to the children far outweigh the costs to parents and the time spent by children in schools.* Parents also need to be convinced that the sacrifice of free labor on the family farm is worth it. This fundamental equation has been forgotten in some countries. Even in India, where the government claims 100% literacy using a low bar for literacy (being able to sign your own name), the government’s willingness to bolster the education system has been half-hearted. At several points during the Covid19 pandemic, schools were closed while malls, restaurants and factories were open. Most schools in India are not air conditioned and they are well ventilated through open windows. Given the pandemic’s known patterns of spreading, keeping schools open should have been the foremost priority for the Indian government.

It has been noticed, over several years, that students who drop out of school in India rarely return at a later stage in life. Their chances at social mobility are affected significantly, and they are stuck doing low productivity jobs such as being a car mechanic or a repair technician: Their literacy helps them with these jobs which involve a lot of traveling in the hot sun but no gaining of knowledge or marketable skills. Their limited experience with formal education limits their ability to grow further, such as setting up their own repair shop or employing a few people in order to run a service business.

The advent of the gig economy has been seen as a boon by many, because most workers in the gig economy need only a driving license and do not need any skills as such. But this could end up becoming the reason for an increasingly literate society to regress back to its illiterate origins. The temptation of quick money made by delivering orders for food delivery apps often overcomes the long-term benefits of education. The Indian government should clamp down on the gig economy by introducing strict requirements for contractual workers, including limits on working time and minimum wages irrespective of demand.

Adaptation of Imported Technologies

This is one of the key concepts in this book. Due to reasons that Allen goes into in detail, the “Standard Model of Going from Middle Income to Higher Income” is no longer viable.

Here’s an obvious statement: Inventions can not be transported as-is across time or space. The new technology must be adapted to local conditions before it can be used widely and create economic development. How many governments are nimble enough to notice this? Not many, as Allen elaborates.

Japan was a country which had a lot of cheap labor. Labor saving inventions were discarded immediately, because they did not solve any existing problem. Instead, while the cotton mill was powered by steam in England because coal was cheap there, it was powered by humans in Japan. While mills were run for only 12 hours a day in England due to the culture of labor laws there, in Japan, the mills were run for 24 hours through 2 shifts of employees. (Once again, as labor was cheap in Japan, it made sense to hire people. Whereas in England, the limiting factor was labor and there was no point in running the mill for 24 hours because the extra labor was too expensive for the final product to be cost-effectively produced.)

India, on the other hand, was a part of the British Empire. India did not implement the 24-hour mill adaptation. Thus, even though labor was cheap in India, the mills were idle for half the day. This hampered the growth of the cotton industry in India, as the capital invested in these mills sat unused for half the time and took twice as long to pay back dividends to their owners.

In his discussion of why industrialization began in Europe and why England had an advantage, Allen points that England had 2 things which were not there in any other Northern European economy:

- Cheap capital (to invest in new technologies and machines)

- Cheap coal (to power the new technologies and machines)

These two advantages were decisive and enabled the start of the industrialization. On top of this, labor was expensive relative to capital and coal. So, businesses found it lucrative to invest capital in machines and train their workers and increase each worker’s productivity, as compared to hiring more workers.

Big Push Industrialization

As we saw, the Standard model for economic developments is defunct now. So, what is the solution?

Allen is optimistic: He says that Asia’s economies have grown through Big-Push Industrialization and that other economies can, too.

The structure of Big Push Industrialization is inherently unstable because it is based on a leap of faith.

- Procure cheap capital

- Build everything that is required for industrialization simultaneously (i.e. Capital is invested in steel production and automobile production at the same time.) Make a leap of faith that the dependencies of every effort will be completed in time.

- Institute a planning authority that reinforces this faith. (i.e. It convinces car manufacturers that the steel they require will be produced domestically by the time they have figured out how to produce a car. It allocates funds to the steel industry to make sure that this promise is actually met.)

4 Asian economies employed this model successfully and closed the gap to the West in a single generation: Japan, China, Taiwan, and South Korea.

Japan

After World War 2, Japan closed the gap to the West in a single generation. Between 1950 and 1990, average annual growth rate was 5.9%.

The products that were being produced were steel and automobiles. State-of-the-art steel production technologies were imported. These technologies were capital intensive, but making a leap of faith, the capital was invested with the belief that there would be a market for the finished good. When the steel was used to produce automobiles, these factories were forced by central planning to be of at least Minimum Efficient Size. The produced cars were exported to America and caused a crash for domestic automobile production in the US.

This would have been a terrible result for any other economy, as the US could have easily imposed import tariffs and prevented Japanese cars from appearing on US roads. But Japan’s delicate position in Asia as a US outpost guaranteed its freedom to trade its goods in the US. After the Second World War, America had emerged as the most competitive economy. Japan’s fortune in securing its place as a seller in the American economy ensured demand for its cars.

China

No modern success story comes close to China’s. Production per capita in China went from $284 in 1988 to $10,500 in 2020. This 36-fold increase in 32 years is phenomenal and unmatched in any other economy of comparable size.

These are not just statistics, either. The effect on people has been stunning too. The percentage of population living below the global poverty line of $1.90 per day went down from 66.3% in 1990 to 0.1% in 2019 in China. Meanwhile, during the same period in India, the value went down from 50.6% to 22.5%.5

Switching from percentages to absolutes, we see the number of people who are affected. This table shows the number of people who were below the poverty line in 1993 and 2011.6

| Country | 1993 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| China | 668 million | 106 million |

| India | 441 million | 281 million |

In 1992, Central Planning was abolished in China. The remaining state forces guide the energy and heavy industry economy, which continue to be central to China’s growth. Both of these have grown constantly since the 1970s. Per capita income grew a whopping 6.7% every year between 1978 and 2006.7

Communal ownership of land meant that agricultural progress and its successes were more equitably shared across China. In India, small farms were pushed out by businessmen who had easier access to capital and could employ the latest innovations easily. China has managed to keep farms of all sizes alive, while small farms in India have retreated back to a subsistence level of life. The government has also had to step in and invest a large chunk of its capital into supporting farmers, the largest voting bloc in India.

As China comes closer and closer to the technological frontier, the state has been loosening its grip over enterprises so that market factors can gain control and enterprises are nimble to changes in the market. If this trend of adaptation continues, then China’s businesses and the Chinese Communist Party should be able to navigate the next phase of the country’s economic development successfully; possibly returning China to the place it occupied in the world, before Vasco De Gama and Columbus set out to find the new world, as the largest manufacturing economy in the world.

Africa’s Woes

The most popular argument I have read about why Africa remains the least industrialized continent relates to geography and its history. Allen puts forth a similar convincing argument: Geography and Colonialism.

Geography matters a lot. And in particular, the proximity to Northern Europe mattered the most. The ability to have a flourishing sea trade with Europe was the deciding factor for growth after the Industrial Revolution because Northern Europe was the most advanced region on the planet and reliable demand for your goods there would be a confirmed ticket into the global economy. However, the sea trade between Africa and Europe never flourished because the distances were prohibitive. The same fact affected South America. South America’s sea ports were farther from Northern Europe than those on North America’s Eastern coast (such as Philadelphia.) So, if the same product was to be exported from both ports, the demand would undoubtedly be higher for the export from Philadelphia because it was closer to Europe.

Colonialism in Africa started in 1800s and split up the continent by the late 1800s. The most common problem was that European imperialists split up African countries into cities and tribal regions. The cities were ruled directly by the imperialists, whereas the tribal regions had village chiefs as before. The imperialists also set up low tariffs to ensure that European goods would be imported and sold to Africans, and nothing would be produced locally. The effects of colonialism were much worse in Africa than in any other part of the world.

Land expropriation was also another huge problem for the African natives. Before the imperialists, land in Africa was basically worthless. Little effort was required to cultivate the land, so most communities were able to sustain subsistence levels of living without much effort. However, once the Europeans had established their rule on the continent, they started taking land away from the natives through imperialist decrees. For e.g., the British passed an act which gave 2/3rds of South Africa’s population the right to lease only 7% of the land in that country.

So, a combination of low tariffs and low wages have pushed Africa into a trap which it has found impossible to get out of. Wages remain low, productivity remains low too. Most of the cocoa in the world is produced in Africa, but export prices continue to be low. There is no incentive to improve productivity or to employ technology instead of manual labor when wages are low. Africa’s story is a depressing one: It is the story of a continent which was unable to escape the Middle Income Trap.

-

“40 pounds” in Allen’s original text. ↩

-

“1 pound” in Allen’s original text. ↩

-

The accurate statement here would be that per-capita value addition to GMV does not rise. The absolute amount of product produced does increase owing simply to medical expansion increasing the life expectancy of people and due to population growth. ↩

-

2011 was the year of the last census in India. No data for poverty in India after this census has been released. The choice of 1993 and 2011 is because these are the only 2 years when data is available on World Bank for both India and China. I made the calculations of “number of people in poverty” by multiplying data from the World Bank for “Poverty headcount ratio (% of population)” and “Total population”. (TSVs of Calculation: China and India: Poverty Headcount (TSV), China’s National Income Per Capita (TSV)) ↩